In 2009 I was at a crossroads of sorts. I had been the pastor of NAPC for five years and was graciously given a three month sabbatical. This gave me the time and room to consider the course I was charting as a pastor and leader. Up to that point I had been a preacher in the line of the mainline Presbyterian tradition, telling stories, sprinkling in anecdotes and asking many open-ended questions, and connecting all of that to the Bible passage of the day that I had chosen. Not that I was contradicting the Scriptures or teaching terrible and false doctrines, but my training and my mentors had taught me to be adept at carefully leaning away from hard teachings in the Bible (by example more than explicitly). This was not at all strange in our denomination, and relative to the rest of the churches in our Presbytery I was still theologically conservative. But I was careful, and I was always thinking about how to soften any Bible body blows so that newer people would not be turned away and regulars wouldn’t be offended.

This was the era of a brand-new phenomenon: internet sermons that were uploaded so that the general public could listen to them. On my sabbatical, I devoured dozens of sermons. I would pull up church websites on my desktop, connect a wire, attach my iPod (not iPad, iPod), and wait 10 minutes while a few sermons were slowly downloaded. I would mow our lawn and listen, or drive to the store and listen, or go running and listen. And what I heard, along with what I was reading over that summer, changed my life and my ministry.

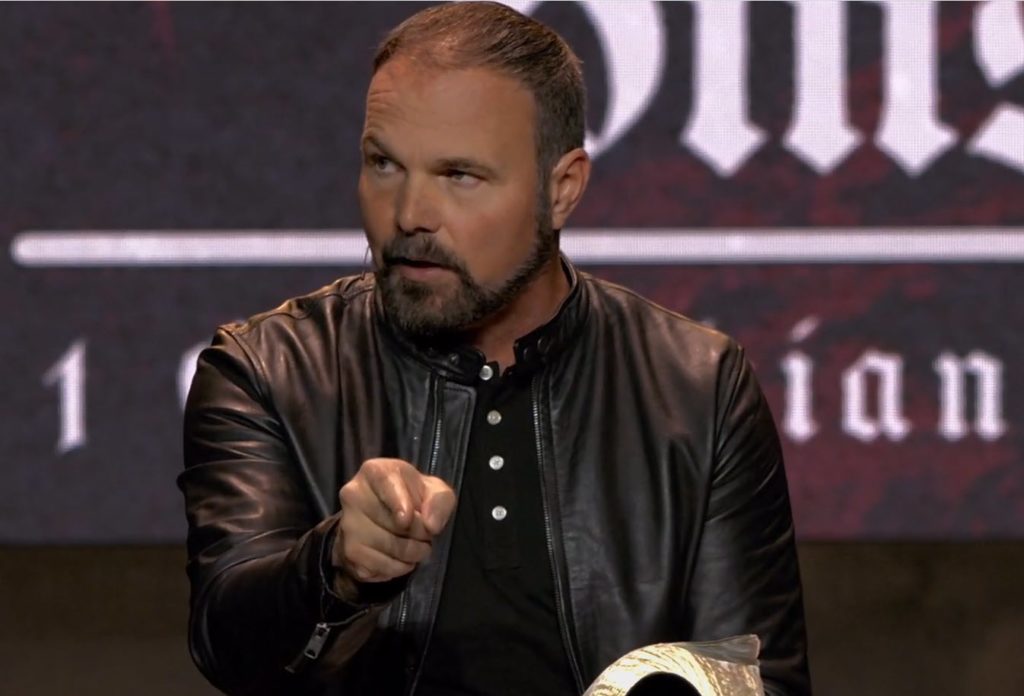

There were several preachers that significantly influenced me with their so-called “expositional style” (preaching through the Bible verse-by-verse and book-by-book) – John Piper and Tim Keller were significant. But one guy’s preaching content and style held my attention and fascinated me more than anyone else – a pastor who was only a couple years older than me by the name of Mark Driscoll. Driscoll had planted a church in secular Seattle that had grown rapidly with its punk-rock aesthetic and its emphasis on reaching rudderless young men wasting their lives on porn and video games. By all appearances it was working. And his preaching style was wild. Topics that I had carefully sidestepped or eschewed he took on like a bull in a china shop. He was brash, brave and bold. Sure, he sounded arrogant and self-centered at times, and there were things he said that were downright inappropriate and wrong to say from the pulpit, but I overlooked that because I was inspired by his courage. He talked about hell, about predestination, about men leading their homes spiritually. He told young men to quit using women, to get a job, get married and have children. And he communicated all of this with the style of a shock-jock stand-up comedian. It was weirdly compelling (in large part, I think, because he was so vastly different from me).

He was only one voice of many during that sabbatical (Piper, Keller, John Calvin and Augustine were others), but the aggregate influence of all I read and listened to convinced me that I had been unfaithful in my preaching and teaching style out of a desire to please people and not offend. I returned with the conviction that I needed to preach and teach books of the Bible verse by verse in order to teach what the Scriptures teach. Mark Driscoll’s ministry was an important influence in that shift for me.

I write this because recently I have been listening to a longform podcast series called “The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill,” by Christianity Today. It traces Driscoll’s rise to fame, the church’s rapid growth in numbers and locations, only to be completely wiped off the map by Driscoll’s resignation in 2014 after being unwilling to receive correction for his abusive leadership style. There had been multiple problems leading up to his final break from the church (from plagiarism to ethically ambiguous book promotion strategies to allegations of spiritual abuse). When he was forced to take six weeks of leave, he never returned to Mars Hill, unwilling to submit to the process laid out for repentance and restoration. Nine weeks after his resignation, Mars Hill Church, with its 15 locations, dissolved.

This story fascinates me. I hope it is not the salaciousness of it, or the dark instinct to revel in the fall of someone successful and famous. The truth is that part of me envies the incredible gifts a man like Driscoll possesses – the charisma, the leadership style, the brilliance, the knack for making everyone in the room laugh. But there is a real danger in elevating these gifts above all other things, in particular character. One of the themes of the story is that again and again, Driscoll was elevated into more and more fame and notoriety because of his charisma, and he lacked the necessary character to handle it. As the podcast points out, this is by no means unique. In the last ten years, many celebrity pastors have been ruined by scandal, by cover-ups exposed, and by tragedy after going through some kind of fall (Carl Lentz, James McDonald, Perry Noble, Darren Patrick, Bill Hybels, and Tullian Tchividjian are only a few).

All of this is relevant for us. The impulse to have an impact in our world, to want to accomplish great things, and to use the gifts we have been given by God to bless the world around us and honor Him – these are virtuous aims and have resulted in incalculable human benefit. You can’t set out to be average if you want to develop antibiotics or write one of the greatest novels of all-time or invent an electric car. Or, to have a strong, influential church that grows and blesses the world around it. But if ambition is for personal fame and wealth only, bad things happen.

As a pastor, the model of ministry I have in mind is really important – am I the ambitious, charismatic teacher/preacher/leader who builds a personal brand, who rises up to influence thousands and to be adored by all? Or am I a hard-working humble servant, leading alongside fellow elders, caring for souls, patiently working the soil, rejoicing when the ground bears fruit and persevering in times of trouble? Is the goal fame or faithful fruitfulness? The second one is Biblical; the first one is nowhere to be found in the Bible’s pages.

We ought to be very ambitious – for God’s glory and for the blessing of and service to the people around us.

Jesus told the parable of the talents because he wants us to use the gifts we have been given in the most ambitious ways possible. This requires dreaming big, strategizing about how to succeed, taking risks and working hard. But if the goal of all that is self-aggrandizement and celebrity, we are in trouble. Character first, then charisma. Faithfulness first, then fruit (and maybe even fame, although fame won’t do us much good judging by what it does to famous people). We ought to be very ambitious – for God’s glory and for the blessing of and service to the people around us.

The best we can do, no matter how many talents we have been given, is to hear a simple line of commendation from the only VIP who truly matters: “well done, good and faithful servant.”

Pastor David